CONTENTS

OCEAN AND MARINE LIFE

- THE ARCTIC OCEAN AND THE OCEAN CURRENTS

- GENESIS OF THE ARCTIC OCEAN

- ARCTIC PLANKTON

- MARINE BIODIVERSITY AND FOOD WEB

- WHALES AND OTHER CETACEANS

- SEALS AND WALRUSES

TERRESTRIAL LIFE

- POLAR FLORA

- POLAR FAUNA

- THE POLAR BEAR

- ARCTIC BIRDS

- SPECIES EVOLUTION AND CLIMATE

HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY

- GEOGRAPHY OF THE ARCTIC REGIONS

- GEOGRAPHIC NORTH POLE, MAGNETIC NORTH POLE

- WHO OWNS THE ARCTIC?

- THE EXPLORERS OF THE FAR NORTH

- THE INUIT

- OTHER PEOPLES OF THE FAR NORTH

- THE ARCTIC TODAY

ARCTIC PLANKTON

The term plankton is used to describe a group of organisms that live in water and are carried along by ocean currents without the means to swim against them. Plankton can be flora (phytoplankton, made up on uni-cellular algae) or fauna (zooplankton: eggs, larvae, small animals, gelatinous creatures, etc.).

PHYTOPLANKTON: THE FIRST STAGE IN MARINE LIFE

The algae component of plankton grows in the surface water, down to a depth of a few dozen metres, where the sunlight is still strong enough to allow photosynthesis to take place. Like land-based plants, phytoplankton needs both mineral elements and sunlight to be able to grow. There are thousands of different species of planktonic algae, all of them microscopic. They comprise the lowest link in the marine food chain.

ZOOPLANKTON

Zooplankton includes representative of most groups of marine fauna, from unicellular animals to jellyfish with “umbrellas” more than 2 metres across. But the stars of the zooplankton world are crustaceans: minute copepods that are among the most numerous creatures on Earth. And of course the “phony prawns” more properly called polar krill.

PLANKTONIC LIFE IN THE ARCTIC OCEAN

During the polar night, planktonic algae stop growing for lack of light. When the thaw begins, the nutritious elements in the water are enriched by the addition of seawater and various organisms that were trapped in the sea ice, and by input brought by the currents and coastal run-off. When the sun returns, marine life reawakens and the food chain starts to function once more. By the time summer arrives, microalgae are even growing underneath and inside the sea ice.

PHYTOPLANKTON FLOWERING

The growth of marine plants is never limited by a lack of CO2 or water. But if they are to build up their living matter they also need light and nutriments – nutritious elements such as phosphates, nitrates, oligo-elements, etc. Unfortunately, the only zone where there is enough light is the surface layer, even though there is nutriment much further down. Nutriment is not just found in coastal waters that are fertilized by input from run-off and rivers, there is also an abundant supply of food in deeper waters because organic matter falls from the surface layers to be recycled by bacteria.

Ocean zones where phytoplankton (diatoms, flagellates, etc.) will proliferate are usually the zones where the nutriments are found close to the surface where light can penetrate (shallow waters or else deep waters where upwellings bring the nutriments to the surface).

PRIMARY PRODUCTION IN THE OCEANS

Oceanographers estimate the amount of vegetal plankton (biomass) present at any given moment in an oceanic region by measuring the chlorophyll content of the seawater. The amount of vegetal biomass in the ocean, almost totally made up of microscopic algae, is a thousand times less than terrestrial biomass. On the other hand, phytoplankton multiplies very rapidly: just one diatom, with two cellular divisions every 24 hours, can generate a million descendants over a period of 10 days. Just compare this to a tree in a forest, which can sometimes take 100 years to reach maturity… Because of the rate at which planktonic algae multiply, primary production in the world’s oceans – calculated by measuring the carbon 14 absorbed by photosynthesis – can be similar to terrestrial biomass production: a hectare of ocean produces anything from 200 kg to nearly 2 metric tons of carbon each year, depending on the region, while a field of corn (maize) produces 2 metric tons of carbon per year.

SATELLITE OBSERVATION

There are still a lot of gaps in scientific knowledge of the productivity of the oceans; certain zones have still to be explored and we still do not fully understand the growth processes involved (deficiencies, water agitation, etc.).

Satellite monitoring, which provides data on wind strength, current speeds, sea conditions (roughness…), water temperature, chlorophyll content, etc.) is an invaluable aid to gaining a better understanding of oceanic plankton “flowerings”.

KINGS OF THE ZOOPLANKTON WORLD: CRUSTACEAN COPEPODS

It is estimated that every litre of seawater contains between 1 and 10 copepods. These minute crustaceans have a body like a grain of rice, legs shaped like oars, sometimes a fairly well developed eye (more like a telescope that a human eye) and outsize feelers.

There are about 2,000 species of planktonic copepods, ranging in size from less than a millimetre to several centimetres, depending on the species. They can be blue or red, colourless or luminescent, benthic or pelagic, polar or tropical. As they are so important to ocean life, they are the focus of numerous biological studies: species identification, studies of stomach content, estimation of daily food intake, determination of growth factors, oxygen consumption, fertility, etc.

KRILL, OR “PHONY PRAWNS”

Krill is the Norwegian word used to describe large concentrations of euphasia, small crustaceans that look rather like prawns (and were for a long time classed as prawns) but that retain numerous characteristics of primitive crustaceans. World krill stocks have been estimated at some 500 million metric tons. Krill are not planktonic, in the strict sense of the word, because they can swim. They move along at 0.5 kph in a school and even faster than 2 kph on their own. Because of this, some specialists classify them as macroplankton while others regard them as microplankton (from the Greek nektos, creatures that swim like fish and cephalopods, etc). In addition, krill migrate vertically within the top 100 metres of the water column, sometimes going even lower in search of nutriments that they filter from the water using a very fine comb-like organ.

BIO-POVERTY OF THE CENTRAL ARCTIC OCEAN

In the central part of the Polar Basin, production of phytoplankton is very low: less than 100 mgC/m2/day. Production in the surrounding strip (the continental shelf) is not much higher, at 150 mgC/m2/day. The zones that open onto the Atlantic and the Pacific (Scandinavian Basin, Baffin and Labrador Seas, vicinity of Bering and the Aleutians) are much richer (200-500 mgC/m2/day) and the coastal waters produce more than 500 mgC/m2/day.

However, it should be borne in mind that these are average values that mask local, seasonal and even annual variations. Nevertheless, the central part of the Polar Basin is always one of the poorer zones.

By comparison, primary production in the Western Mediterranean is 100 mgC/m2/day (ça devrait être 1,000?) and 10,000 mgC/m2/day in the exceptionally rich strip along the coast of Peru.

THE LIFE OF ARCTIC PLANKTON IN SUMMER

Biologists have put forward several hypotheses to explain the life of Arctic plankton.

In spring, the melting ice produces a desalinated and stable layer of water on the surface of an ocean rich in nutritious salts. This phenomenon allows micro-algae to start to multiply. The growth and recycling as waste of certain species subsisting in the ice underneath the pack provides some of the “ingredients” needed for this.

In the Barents and Norwegian Seas, the life cycle of the first “generation” or wave of the dominant copepod species (Calanus finmarchicus and C. glacialis) shows that the beginning and end of hibernation (more properly diapause in deep water) of the copepods, the growth of their genital organs and the moment of egg-laying seem to be determined by the need for the first (herbivorous) stages of the life cycle to be synchronised with the growth of surface phytoplankton in the surface layer.

In the Greenland Sea, the water coming out of the Arctic Ocean contains little zooplankton. In this zone, only the waters mixed with Atlantic water, carrying copepods and probably other species (microphagous species such as salp) can introduce herbivorous grazers. So phytoplankton is very abundant there.

WHAT HAPPENS IN WINTER ?

BIOLOGIST’S CORNER

SOME USEFUL VOCABULARY

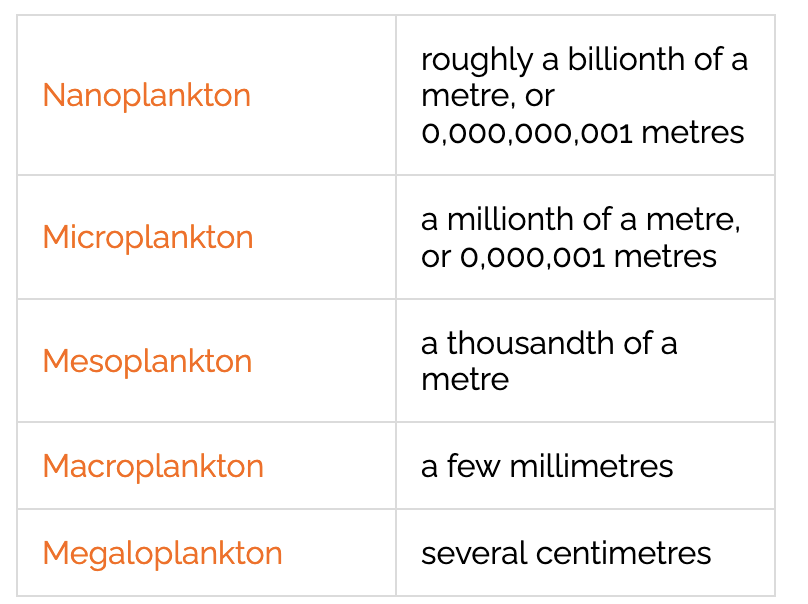

Planktonic organisms can be classified :

– By size

– By their position in the water column. Organisms on the surface are called epiplankton. This is where most of the better-known organisms live (copepods, small prawns, etc.). Organisms that live in the depths are known as bathyplankton. These are large transparent animals, filter-feeders like jellyfish, that can best adapt to the bio-poverty of this environment.

– By their position in the water column. Organisms on the surface are called epiplankton. This is where most of the better-known organisms live (copepods, small prawns, etc.). Organisms that live in the depths are known as bathyplankton. These are large transparent animals, filter-feeders like jellyfish, that can best adapt to the bio-poverty of this environment.

By their adult form. When an organism spends only the larval phase of its life cycle floating in the water (e.g. the larvae of sea urchins, benthic fish, worms, etc.) they are called meroplankton.

The other type is holoplankton, or animals that spend their whole life cycle in a planktonic state (foraminifera, radiolarians, copepods, chaetognaths, etc.).

TO FIND OUT MORE …

BIBLIOGRAPHIE

- L’Arctique et l’environnement boréal, P. Avérous – CNDP, 1995

- L’Antarctique et l’environnement polaire (2) “EREBUS” ,P. Avérous – Dossier pédagogique – CNDP-1992

- Chercheurs sur l’Océan”, P.Avérous – Hachette -1981

- Les missions de l’Antarctica : la traversée de Pacifique -1994

- Arctic Flora and Fauna : status and conservation (CAFF, Conservations of Arctic Flora and Fauna, Helsinski Edita, 2001)