Polar Encyclopædia

THE INUIT PEOPLE

LIVING AROUND THE ARCTIC RIM

For centuries, the Inuit were a nomadic people who spent their time hunting and fishing, but today they have become sedentary. There are more than 125,000 Inuit belonging to about 40 different ethnic groups living in an enormous area that includes parts of Alaska (United States), Canada, Greenland (Denmark) and Russia. Even though groups of them may be separated by huge distances, the Inuit have remained remarkably homogeneous.

INUIT OR ESKIMO ?

The word Eskimo, meaning “eater of raw meat” in the language of the Algonquin Indians, was first applied to them by French settlers in the 17th century. Today, they are described by their more local names (Yupik, Inupiat, etc.) or by the more generic term Inuit (a plural noun of which the singular is Inuk), which means “the people”, as defined by the first meeting of the ICC in Alaska in 1977.

PERFECTLY ADAPTED TO THE CLIMATE

The Inuit have learned to make do with what their difficult environment offers them: polar animals, ice, stones, etc. Their staple diet is the fat and meat of seals, rich in iron and vitamin A, which helps them withstand the cold. But above all they have adapted culturally: their clothes, snow-shoes, dog sleds, kayaks, hunting strategies etc. are all purpose-designed for the Arctic.

BETWEEN TRADITION AND MODERNITY

Hunting and fishing remain the basis of the Inuit civilisation. In return, they treat Nature with great respect. Today, the confrontation with the modern world sometimes proves difficult (alcoholism, suicide…), but in general they have learned to use modern tools (Inuit-language papers and magazines, Internet, snow-scooter, aircraft) to cement their future. In Canada, the Inuit have managed their own autonomous territory, Nunavut, since 1999.

BERING STRAIT, CROSSROADS OF THE FIRST ESKIMOS

About 5,000 years ago, several groups of people settled on each side of the Bering Strait, which during that era was free of ice. The region attracted hunters of various origins because it offered a rich variety of fauna both on land and in the sea. It is in this region that the first traces of the Eskimos’ ancestors have been found.

A thousand years later, the ice caps of the American continent melted and the hunter communities along the Bering Strait migrated southwards in America and along the Arctic coast as far as Greenland.

Pre-historians studying vestiges and fossils from this era use the term Eskimo to describe “hunter peoples that adapted to the coastal resources of the Arctic”. This era is divided into two major prehistoric periods and cultures: Paleo-Eskimo and Neo-Eskimo. It was the latter branch that spread out across the whole Arctic; they are the ancestors of today’s Inuit.

TRADITIONAL LIFESTYLE BASED ON HUNTING

Until about 30 years ago, the Inuit depended entirely in hunting, not just for their food but also for materials to make tools, build shelters and make clothes. Their lifestyle meant they were able to draw a subsistence livelihood from their fragile natural environment without unbalancing it. In winter, the Inuit hunted marine mammals (seals, walruses and cetaceans) and in summer they moved inland from the coast hunting caribou, fishing in the rivers and lakes, snaring birds and taking their eggs, and gathering berries and herbs. The men hunted, made tools and built kayaks while the women prepared animal pelts, sewed clothes, dried meat, looked after the children, fished and gather lichen, seaweed, etc. The Inuit also left plenty of time for amusement (playing jacks and cup-and-ball, telling stories, dancing…).

HUNTING FOR CARIBOU…

The Inuit used every part of the caribou they killed, the meat for food of course, but also the hide, which was used to make clothes, blankets, tents and kayak skins. The tough skin from the animal’s forehead was used for shoe soles and the softer skin from its belly for making leggings. A parka needed four caribou hides and a pair of pants required two more. The antlers were used to make tools, the tendons made sewing thread, and the fat was rendered to make lamp oil.

…AND MARINE MAMMALS

Hunting marine mammals such as seals called for real teamwork so that the Inuit could spot them, follow them, kill them and cut them up. In winter, dogs would sniff out the mammals’ breathing holes in the ice pack and then the hunters would lie in wait, and as soon as a seal came up for air it was harpooned. In spring, mammals could be killed while they sunned themselves on the rocks or ice, and in summer they were hunted at sea using kayaks.

Seals were a favourite prey because their meat was so nourishing, but the Inuit also used the mammal’s waterproof skin as well as its bones. Similarly, whenever the Inuit managed to kill a whale, they used practically every part of it: the blubber was used for food and for oil to heat and light their homes, the whalebone or baleen was used to make bows for hunting, and the bones themselves were used to make sleds.

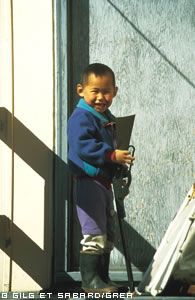

SOFT EDUCATION IN A HARD MILIEU

Traditionally, Inuit parents brought up their children with kindness and patience. It was regarded as unacceptable to strike or even to reprimand a child. Experiment and imitation were regarded as the best apprenticeship, and most knowledge was transmitted orally. The most prized traits of character were generosity – which was usually rewarded – and kindness. In a society underpinned by cooperation between members, these were indispensable qualities. Any show of anger was regarded as shameful, as an impulsive gesture could threaten the very survival of the community. Social pressure was the basis of education. Any display of ill humour was ridiculed, and one of the most severe punishments for a child was to be given less affection. And in a society so dependent on cohesion, the greatest pressure on an individual was the threat of banishment from the group.

ADAPTING TO THE ARCTIC COLD

The Inuit have adapted both technically and culturally to their extreme environment. But over the millennia they have also undergone physiological changes. The average Inuk’s body has become stockier, his hands and feet smaller and his face is rounder and flatter than the features of people living in more temperate climes. And all these characteristics reduce heat loss. It also seems that their basic metabolism is higher, and thanks to their exceptional capillarity, their blood-flow maintains an even balance between the heart and the body’s extremities. Lastly, the Inuit diet is particularly well suited to their lifestyle.

A DIET WELL SUITED TO THE COLD

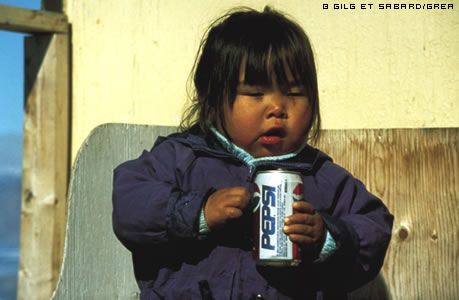

Since 1945, contact with the modern world has changed the eating habits of the Inuit, increasing the proportion of carbohydrate in their diet. Nevertheless, they still value “real food” – food provided by their own environment – above all else. For the two thirds of the Inuit population that eat what they hunt, nearly 80% of calorie intake still comes from local resources (marine mammals). In winter the ringed seal is their main source of fresh meat, but in summer their resources are more varied: they hunt migratory mammals (hooded seals, Greenland seals, narwhals, beluga, right whales) and store any surplus meat for winter, and they also derive plentiful calories from fishing (bullhead, arctic char, salmon, polar cod).

Nutritionists have long wondered how the Inuit diet, very rich in animal protein, could be sustainable because the excess nitrogen generated by over-consumption of meat can lead to serious health problems caused by certain metabolic residues such as uric acid. In reality, the fat of marine mammals, eaten along with the leaner meat, ensures that the Inuit do not suffer from the problems usually associated with over-consumption of meat. In addition, most of the lipids they consume come from marine mammals and fish and so contain a high proportion of unsaturated fatty acids, which hardly raise the cholesterol level at all.

THE INUIT AND THE MODERN WORLD

For the Inuit, contact with the modern world has meant an abrupt transition lasting only about 30 years. Their lifestyle today bears little resemblance to that of their grandparents. Their kayaks have been replaced by motor boats, they live in wooden houses instead of igloos made of snow or earth, they use guns instead of harpoons and travel on snow-scooters instead of dog sleds.

Not only that but the Inuit live in real villages that they share with “foreigners”. Some of them have paid jobs and the rest live off welfare. This change of lifestyle has destabilised the Inuit, above all the younger generation, and a combination of frustration and depression have brought hitherto unknown social ills: alcoholism, suicide, violence, delinquency… Nevertheless, many traditions survive: a sense of “extended family”, the links with Nature (including some vestiges of shamanism), the need to talk things over before making decisions, a taste for traditional Inuit activities such as sports and games, and a desire to keep on speaking the language of their ancestors.

INUKTITUT, THE INUIT LANGUAGE

Until the 18th and 19th centuries, when the first missionaries arrived in the Deep North, the Inuit language was spoken but never written down. It is a so-called agglutinant language, in which ideas – represented by words – that could form a sentence are lined up after a stem-word. For example, “we really want to build a big house” is expressed as iglualuliurumatsiaqtugut, or house-big-build-want-really-we. The Inuit language is very rich in words related to Nature. For example, there are a dozen words that can be used to say snow because the characteristics of snow can vary so much according to atmospheric conditions.

In fact there is no single Inuit language but numerous dialects, because groups of Inuit have always been widely spread geographically with very little communication between groups. But all dialects can be understood by all Inuit.

Even today, there is no written language common to all. The Inuit use three different alphabets: the Cyrillic alphabet in the Russian north, the “Roman” alphabet in the West, and a rather peculiar “syllabic sign” system worked out nearly a century ago by a Canadian priest. This system is now being used more and more widely.

LIVING AROUND THE ARCTIC RIM For centuries, the Inuit were a nomadic people who spent their time hunting and fishing, but today they have become sedentary. There are more than 125,000 Inuit belonging to about 40 different ethnic groups living in an enormo

Today, each Inuit village in America has a cooperative that buys pelts and handicrafts, particularly the famous Inuit carvings from walrus tusks, whale bones the antlers of caribou or musk ox and the well-known soapstone (steatite). But while the tourists see an aesthetic value in them, the Inuit who make the artefacts see a spiritual (animist) value: “The Inuit listen to the stone describing the shape it contains before they carve it” (M. Noel).

I am nothing but a stone

But I want to become money

So I will go visiting.

Message in Stone. Sculpture by an Inuit from Ivujivik (Hudson’s Bay), Tivi Paningayak (1990).

TOWARDS RECOGNITION OF THE INUIT NATION

For the Inuit, one of the main obstacles to accepting modern western society – and its emphasis on land ownership – is their notion of collective ownership of territory. “This is where we all live, so it is territory that belongs to all of us, which makes land disputes between neighbours quite pointless”.

For the Inuit, the resources to be found in the earth or the sea – whichever state may claim sovereignty – belong to everyone, even though people may be spread over an immense area. The Inuit assert with determination that “We are a peace-loving people who believe that humankind is made up of myriad civilisations and nations who, if they act as one, can bring hope and security to Life itself”. (Aqqaluk Lynge).

A SHORT HISTORY OF THE INUIT PEOPLE

In 1969, at the initiative of Jean Malaurie, a first international gathering of Inuit from Canada, Alaska and Greenland was held in France.

Even before that, in 1962, Canada’s Inuit had been given the right to vote and in 1971 they founded the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada (ITC), an association intended to put the Inuit point of view on issues such as the economy, the environment, the education system, etc.

Meanwhile, in Alaska the Inuit, the Amerindians and the Federal Government reached an agreement paving the way for the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA).

In 1966, in Canada, the James Bay and Northern Quebec Convention was signed by the Nunavik Inuit and the Cree Indians, agreeing to the “industrial valorisation” of their territories.

In 1979, in Greenland, the Kalaallit people gained the right to self-government (set up in their capital, Nuuk). In the only compromise of its kind ever recorded, the people of Greenland regained their lands, although the agreement also provides for management of any mineral resources to be shared with Denmark, with a double right of veto.

On 28 June 1980 the Inuit living in America, Canada and Greenland, meeting in Nuuk, set up their first international body – the Inuit Circumpolar Conference (ICC) – which was officially recognised by the United Nations in 1983. The Yupik of Siberia, which formed their first association in 1990, subsequently joined the ICC too.

In 1984, the Inuvialuit living in the Mackenzie River delta also signed an agreement along similar lines to the James River Convention.

TOWARDS AN INUIT COMMON MARKET

Greenland (with a population of 60,000 living in an area 4 times the size of France) refused to join Europe’s Common Market (EEC). In a referendum, the Kalaallit, reacting against past Danish colonisation, refused to become subject to European fishing quotas. Excluded from the economies of the various nations that they had been part of, the Inuit got together to set up a free-trade zone covering all the territories they occupied, stretching from Russia to Greenland and designed to encourage cross-border investment, industrial cooperation and the unrestricted movement of both people and goods. In attempting to set up this unified Polar zone, the Inuit – with their age-old tradition of exchanges – were also throwing down a challenge by asserting their usufruct of the lands that the “great powers to the South” had formerly divided up between them.

THE INUIT IN FIGURES

There are:

30,000 Inuit in Canada,

44,000 Inupiaq and Yupik in Alaska (United States),

50,000 Kalaallit in Greenland (Denmark),

1,200 Yuit in Siberia (Russia).

DID YOU KNOW ?

> Parka is an Alaskan Inuit word and anorak is a Canadian Inuit word.

> The Inuit are among the most photographed people in the world. Nanuk of the North – a portrait of an Inuk’s daily life – is considered to be the first documentary film in the history of the cinema. The film, made in 1922 by Robert Flaherty, was a huge success and allowed people all over the world to learn about the Inuit for the first time.

> To the Inuit, Europeans – seen as too unstable and worried – are tukuma, or people who simply have too much to do.

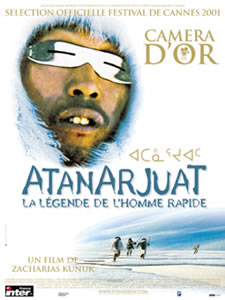

> The first Inuit film, Atanarjuat, the fast runner (Z. Kunuk), was released in France in February 2002 and won a prize at the Cannes festival.

TO FIND OUT MORE …

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Peuples des Grands Nords, Traditions et transitions – Collectif dirigé par AV Charrin, J.M. Lacroix et M. Therrien, Presse de la Sorbonne Nouvelle /INLCO, 1995

- Handbook of North American Indians – David Damas – Smithsonian Institution – 1984

- Ignacio Ramonet – Le Monde Diplomatique – 1989

- P.Robbe – Science et Avenir

- People of Arctic – National Geographic – vol.163 n°2 – février 1983

- Arctique Horizon 2000, Les peuples chasseurs et éleveurs, direction J. Malaurie – Éditions du CNRS, 1991

- L’aventure polaire, cinq siècles de présence française, P.Avérous, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle/Expéditions Polaires Françaises – 1997

- Les derniers rois de Thulé – Jean Malaurie, Collection Terres Humaines – Plon, 1955

- Ultima Thulé – Jean Malaurie, 1990

- Inuit, Histoire de la Conférence Circumpolaire Inuit, A. Lynge – Atuakkiorfik -1993

FILMS

- Inuit, du Groenland à la Sibérie – Jean Malaurie – (La cinq – Teva Victor)

- Between two worlds – 1990 – documentaire (ARTE)

- Nanuk, l’esquimau – 1922 – Robert Flaherty

- Atanarjuat, la légende de l’homme rapide – Zacharias Kunuk – 2002

USEFUL WEB SITE

- http://www.inuit.org/

Support the project with a donation

The Polar POD expedition is one of the stamp of the pioners, a human adventure coupled with a technological challenge, an oceanographic exploration never before carried out which will mark a milestone in the discovery of the oceans.

Thank you for your support !