Polar Encyclopædia

THE OTHER PEOPLES OF THE DEEP NORTH

THE SIBERIANS: “SMALLER PEOPLES OF THE NORTH”

Aleuts, Dolgans, Enets, Evens, Chuktches, Nenets, Koryaks, etc., a large number of less numerous peoples live in the Arctic regions of Siberia and the Russian Far East. A census taken in 1989 showed that together they numbered 180,000 people. As for the Yakuts, they form a distinct group of more than 380,000 people living in the Sakha Republic (formerly Yakutia).

THE SAAMI OF EUROPE

The Lapps, or Saami, live on Europe’s northern rim, stretching from Norway to the Kola Peninsula. Today they number about 70,000, but only 5,000 of them actually live in the Arctic. Even though they are still mainly a nomadic people living from fishing and reindeer husbandry, they have adopted modern technologies. In Russia, they were forced to become sedentary during the Soviet period.

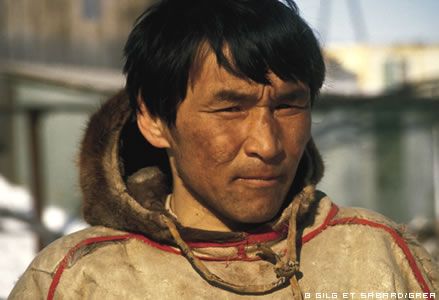

THE PEOPLE OF THE BERING STRAIT

Throughout recent history, the Aleuts living in the Aleutian Islands and the Pribilof Islands of Saint George and Saint Paul have been bundled back and forth between Russia and the United States. Today, there are about 2,000 of them left, speaking mainly American but still earning their livelihood by fishing and hunting at sea. On the continent itself, some Amerindian tribes (Cree, Dene, etc.) also live as far north as the edge of the tundra.

MYTHS AND SHAMANISM

The peoples of the North all live in a very harsh environment and they have all developed a number of similar survival rules such as reindeer husbandry, intra-community solidarity and communion with their milieu (myths, shamanism). Shamanism is a religion closely tied up with the spirits (plants, animals, water, etc.) that live in Nature.

EURASIA, THE FIRST ARCTIC SETTLEMENTS

The earliest ancestors (some 30,000 years ago) of the Amerindians and the people of Eastern Siberia probably lived in East Asia. Traces of their presence have been found in southern Siberia close to the borders with China and Mongolia as well as around Lake Baikal and the high valleys of the Ob, the Angara and the Yenessei.

After the last Ice Age (18,000 years BC), these prehistoric Siberians reached the far north by following the course of the large rivers – which were both lines of communication and sources of food – from the steppes to the Arctic Ocean.

By about 14,000 years BC, these prehistoric Siberians had occupied almost all over the Asian Arctic, settling as far east as the Kamchatka Peninsula in the Far East (Ushki). Tools discovered in various sites have allowed archaeologists to define a specific culture they call the Paleo-Arctic Siberian Tradition. Traces of this culture have been found as far apart as the coasts of Japan (Hokkaido) and North America. Around the 5th and 4th millennium BC, the vegetation in the Arctic became more “people friendly” and the Siberians were able to move even further north hunting, gathering and fishing for food and improving their technical skills (bows, fish-hooks, boats, sleds, skis, etc). They also developed social rites (as illustrated by the scenes drawn on the walls of caves in the region) and they learned how to farm and raise livestock. By the 4th and 3rd millennia BC they were living around the Ural and the Ob as well as in Kamchatka and the Kuriles. Improved ecological conditions meant that prehistoric man could stay longer in one place, and so they gradually became seasonal nomads rather than continuing with their long migrations.

THE SMALLER PEOPLES OF THE RUSSIAN DEEP NORTH

These days, linguistics experts define three major groups of Siberians, with different origins: the Uralic group (in the west, on each side of the Ural) whose language originated in the 4th millennium BC; the Altaic group, in the south-central region on each side of the Lena; and the Paleo-Asiatic group, in the north-east of the Far East (and whose rather ambiguous name suggests that the group may have settled there a long time earlier than the others, which is not the case).

It has also become usual to subdivide these groups, linguistically. The Uralics are split into Finno-Ugrians (including both the Hungarians and the Lapps) and Samoyeds; the Altaics are split into Tunguso-Manchus and Turko-Mongols; and the Paleo-Asiatics are split into the Eskimo-Aleuts and the Yukaguir-Chuvants.

The following, in alphabetical order, are the groups living closest to the Arctic: names, location and population at the 1989 census :

Aleuts (Eskimo-Aleut group): 702 people, living in Russia (Kamchatka and the islands in the Bering Strait). However, most Aleuts are now found in the American Aleutian Islands.

Dolgans (Turko-Mongol group): 6,945 people, living in the Sakha Republic (ex-Yakutia) and in the Dolgano-Nenets okrug (autonomous district) of Taimyr (capital Dudinka). These people have evolved from the cross-breeding between the Tungus, Yakut, Samoyed and Russian populations. They claimed they belonged to the Orthodox Church, at least until the rise of communism.

Enets (Samoyed group): 209 people (i.e. they are fast becoming extinct), living in the Dolgano-Nenets okrugs (autonomous district) of Taimyr and Evenkes (capital Tura).

Evens (Tunguso-Manchu group): 17,199 people, living in northern Yakutia, beside the Sea of Okhotsk, in Kamchatka and in Chukotka.

Itelmens (Paleo-Asiatic group): 1,481 people, living in the south-western part of Kamchatka, towards the Sea of Okhotsk (autonomous okrug of the Koryaks).

Iuits (or Yuits or Yupiks) (Eskimo-Aleut group): 1,719 people, living at the tip of the Chukotka Peninsula (also St Laurence Island and Central Alaska). They are directly related to the American Inuit.

Some groups of Iuit living in the sensitive zone near the border between the US and the USSR during the 1950s were forcibly moved away from their fishing villages (Big Diomed, Naukan, Unazik, etc.) and all had to adapt to 5-Year Plans with quotas for eider and seal catches) that were far removed from their traditional subsistence way of life.

Koryaks (Paleo-Asiatic group): 9,242 people, living in the Kamchatka oblast and the autonomous okrug of the Koryaks (capital Palana).

Along with the other people in Kamchatka, they have developed a very impressive oral literary tradition (myths, folk-tales, etc.). Their written language uses an alphabet derived from the Cyrillic. They are now becoming sedentary but always rebelled against collectivisation and like the Chuktches, they were able to preserve their traditional way of life until the early 20th century.

Nenets (Samoyed group): 34,665 people, living in the Iamalo-Nenets okrug (capital Salekhard) and the Dolgano-Nenets okrug of Taimyr (capital Dudinka) as well as in the European part of Russia (the Nenets okrug in the Archangelsk oblast, capital Naryan Mar). A typical Arctic people, the Nenets are the only people to have reached the Russian archipelagos and settled on Novaya Zemlya, from where they were deported by the Soviets because of “nuclear testing”.

Their distant ancestors came from the Saian Mountains and adapted extraordinarily well to the rigours of the polar climate. Their laws are those of other inhabitants of the tundra: reindeer husbandry and clan solidarity. But under the Soviet regime they underwent sedentarisation, collectivisation and folklorisation… Yet despite all that, some Samoyed still practise shamanistic rites and they have conserved an extraordinary tradition of oral literature. One Nenets woman, Anna Nerkagui, the daughter of reindeer farmers, has complied a written record of Nenets traditions. The first ever film made by a Nenets, The Seven Chants of the Tundra, was released in France in 2002.

Nganassans (Samoyed group): 1,278 people, living in the Dolgano-Nenets okrug of Taimyr. This modest group is the result of contact over the centuries between Paleo-Asiatics, Tungusos and Samoyeds. They live within the confines of the Taimyr Peninsula, sometimes travelling as far as the ocean during their spring migrations, making them the northernmost dwellers on our planet (they live even further north than the Greenland Inuit or the Nenets on Novaya Zemlya). Until the Soviets took power, the Nganassans always remained faithful to their shamanistic beliefs, but today, as they have no written language, they have conserved only part of their age-old beliefs.

Chuktches (Paleo-Asiatic group): 15,184 people (Magadan oblast, autonomous okrug of the Chuktches, capital Anadyr). About 30% of the Chuktches belong to a maritime group, sedentary communities that have settled along the Arctic coast of the Bering Sea. The rest are nomadic people who raise reindeer and live in camps spread throughout the northeast of the Kamchatka Peninsula.

The okrug of the Chuktches, set up in 1930, is now autonomous. The Chuktches have had a written language since 1932 and have developed a literature that is particularly rich. They also boast one of Russia’s best writers, Yuri Rytkheu, who was born in Uelen. During the 1930s, the Soviets deprived them of their traditional means of existence and forced them to adopt a sedentary life on collective farms. Today, the Chuktches are striving to regain their identity.

Chuvants (Yukaguir-Chuvants group): 1,511 people, living in the autonomous okrugs of the Chuktches and the Koryaks.

Yukaguirs (Yukaguir-Chuvants group): 1,142 people, living in the northeast of the Sakha Republic (ex Yakutia) along the Kolyma River.

Yakuts: 381,922 people, living in the Sakha Republic (ex Yakutia). The Yakuts are too numerous to be regarded as one of the “smaller peoples” of Siberia, and should be considered as a people in their own right.

THE FOLKLORE OF THE SIBERIAN PEOPLES

The origins of the cultures of today’s Siberian peoples go back into the mists of time. These cultures have also been enriched by the traditions of other immigrant peoples.

According to Alexandre Soktoev, Director of the Novossibirsk Institute of Philology (and himself a Siberian), “folklore – oral and alive, an everyday thing – teaches the age-old art de vivre of our ancestors. It conveys the desire for harmonious coexistence with Nature, it provides rules for survival in the difficult conditions found in these climes, and it holds secrets that belong to natives of this region and to no-one else in the world. In addition to ecological themes (‘Take only what you need from Nature’), ethical questions are also a major element”. Soktoev goes on to say that “Even in these modern times, folklore plays an essential part in the life of the peoples of Siberia. And for a variety of reasons, deep in their hearts these native peoples feel that their folklore lies at the core of their national consciousness. It is the deepest layer of their culture, and the better they preserve that layer the more upright they will walk on this Earth. There is another factor in play here: most native Siberians – and particularly those belonging to the smaller groups, live in remote places that are still difficult to reach (…) so they are still strongly influenced by their ethno-cultural traditions”.

Autrement, (magazine) special issue, N° 78, 1994)

AND WHAT OF THE FUTURE?

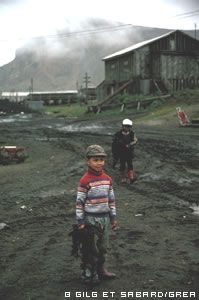

For all these smaller native peoples living in the Russian Deep North, the advent of communism, with its emphasis on creating a “new man”, meant forced sedentarisation and the transition from “responsible” local management traditionally underpinned by the wider laws of Nature (and with shamanism) to management/government based on productivity and central planning. This also meant the colonisation of their territory (for fishing, livestock raising, mining, oil and gas production), short-sighted population migrations, subsidies… The result was that native people were “deprived of their property and their pastures, their flocks of reindeer, their hunting and fishing resources, their dignity and their responsibility for their own lives”. These Siberian peoples “lost their very souls”, their reason to live, and gave way to despair. Their future was aimless existence, child mortality, alcoholism and suicide.

But since Russia has opened its doors to the rest of the world its Siberian minorities have become fascinated by the achievements of the American Inuit and have been trying to assert their own point of view and to organise themselves well enough to manage their own territories. In 1990, the 26 “smaller peoples of the North” held their first combined congress in Moscow and today their representatives take part in all international circumpolar gatherings.

DID YOU KNOW ?

> One site in the Arctic islands was recently recognised as dating back 8,000 years. The site is at latitude 76°N on the island of Jokhov in the De Long archipelago to the north of the Novossibirsk islands. It is the northernmost archaeological site to have been discovered so far.

> The kolkhozes, or collective farms, where the Nenets handed in their fish catch in exchange for a fixed salary have now closed down. As for the Chuktches, they have started hunting whales and walruses for a livelihood now that the State no longer provides them with food.

> The Russian Federation is divided into various political and administrative districts and republics. The following entities have coastline on the Arctic Ocean and are home to 4,289,000 people, of which 3.7 million live in the regions of Murmansk and Archangelsk alone, in the European part of Russia: the Republic of Sakha-Yakutia (the largest, with 3 million square kilometres but hardly more than a million inhabitants, of which 39% are native peoples); the okrugs of Iamalo-Nenets, Nenets, Taimyr and the Chuktches and the oblasts of Murmansk and Archangelsk.

TO FIND OUT MORE …

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- La préhistoire dans le monde – José Garander – puf -1992

- Handbook of North American Indians – David Damas – Smithsonian Institution – 1984

- Arctique Horizon 2000, les peuples chasseurs éleveurs – Colloque 1983 – Ed CNRS – 1991, dir. J. Malaurie

- L’organisation et l’idéologie sociales face aux changements de ressources : exemple Saame, Christian MERIOT – ethnologie et anthropogéographie arctiques – 1982 – ed CNRS

- Le problème de la singularité des Aléoutes : un essai de problématique – Félix Torres – ethnologie et anthropogéographie arctiques, colloque 1982 – ed CNRS – 1986

- Les Sibériens de Russie et d’Asie – une vie, deux mondes – Coll. dirigé par AV CHARRIN – revue Autrement, série Monde – HS N°78 – Octobre 1994

- Peuples des Grands Nords : Tradition et Transition – coll. dirigé par AV CHARRIN, J.M. LACROIX et Michèle THERRIEN – PNS- 1996

- Une saison chez les Tchouktches – Boris Chichlo – Terres Sauvage – n°67 Novembre 1992

- La Nouvelle Russie, l’après 1991 : un nouveau “temps de trouble” – J. Radvanyi – Masson/Armand Colin, 1996

- People of Arctic – National Geographic – vol.163 n°2 – 1983 fev.

- L’aventure polaire, cinq siècles de présence française, P.Avérous, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle/Expéditions Polaires Françaises – 1997

Support the project with a donation

The Polar POD expedition is one of the stamp of the pioners, a human adventure coupled with a technological challenge, an oceanographic exploration never before carried out which will mark a milestone in the discovery of the oceans.

Thank you for your support !